|

|

Best

known for his play The Dybbuk, the famous Yiddish writer

and dramatist S. Ansky (Shloyme-Zanvl Rappoport; 1863-1920) wore

many other hats; he was a poet, socialist activist, emergency aid

worker, and ethnographer. Through the combination of these many

and varied capacities he earned his reputation as a great builder

of modern Jewish culture.

Ansky

was born during the late stages of the Jewish enlightenment (Haskalah),

and at the beginning of the wave of virulent anti-semitism and pogroms

that spawned Zionism in Europe and Russia. Like many other Jewish

writers of his time, Ansky was also involved in social activism;

for Ansky and his contemporaries, the great Zionist and Jewish literary

pioneers of the 20th century, nurturing and creating Jewish culture

went hand-in-hand with Jewish survival.

|

Born Shloyme-Zanvl

ben Aaron Hacohen Rappoport in 1863, Ansky was reputed to be a Talmud

prodigy in his hometown of Vitebsk, then part of the Russian Pale of Settlement

(now in modern-day Belarus).[1]

The town was the center of Habad Hasidism, and also contained formidable

representatives of traditional rabbinic Judaism. But before he was fifteen,

he would reject Jewish religion altogether and

enter the world of ideas, embracing the ideology of socialism. At 17,

Shloyme-Zanvl was running a commune on the edge of town for boys who had

left the Yeshiva. He then spent a year living undercover in a Hasidic

shtetl, attempting to convert its inhabitants away from their religious

beliefs. (He was discovered and chased out by the Czar's police, always

on the lookout for social agitators, real or imagined.)

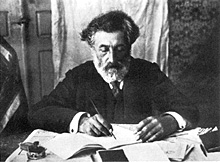

S.

Ansky in 1920

S.

Ansky in 1920 |

Leaving Vitebsk, Shloyme-Zanvl

tutored young Jews in the villages and shtetls of the Pale for

a meager living. Subscribing to the views of the Russian populist party,

the Narodnicki, his goal was to learn about the Russian peasantry and

working class (the narod), a necessary step for a revolutionary

with plans to infiltrate the working classes and spread socialist propaganda.

At age 24, he left the Pale and took a job working

as a miner in Russia, near the southern city of Yekaterinoslav. There,

the workers gave him the name Semyon Akimovich (a Russified version of

his name), which he kept from then onward.

After three years

working with the Russian miners, the Czar's police discovered and expelled

him. Although the hard labor he had endured for three years had ruined

his health, he set out — with his characteristic

energy and resourcefulness — for St. Petersburg,

where he was soon at home among the city's intelligentsia. In St. Petersburg,

Semyon Akimovich wrote for the Narodnicki party's monthly, and his "Sketches

on Folk Literature," based on his experiences with the Russian workers,

was serialized in a leading populist journal. This was the first time

Semyon Akimovich used the name S. A. An-Ski (Ansky). He claimed he had

invented this very non-Jewish name in honor of his mother Anna. By this

time, Ansky was writing only in Russian and had declared the beloved Yiddish

writer Sholem Aleichem "bourgeois" and "parochial."

Forced by the Russian

authorities to leave St. Petersburg in 1892, Ansky settled in Paris, where

he was secretary to the Russian philosopher and revolutionary Piotr Lavrov

for six years. There he lived a bohemian lifestyle, complete with disastrous

love-affairs. He spent time as well in Switzerland, where he was among

the founders of the Russian Social Revolutionary party in 1901. Moving

back to St. Petersburg in 1905, Ansky joined the Jewish Labor Bund, although

he was not yet interested in Jewish nationalism. The Bund's anthem, "The

Oath," which is still used to this day, was written by Ansky.[2]

It was the work of

the famous Yiddish and Hebrew writer I.L. Peretz that caused the dramatic

reversal in Ansky's life that returned him to the bosom of his own people.

Peretz's writing proved to Ansky that Yiddish writing might be considered

modern European literature. Inspired by Peretz and by a newfound passion

for Jewish culture, Ansky began writing in Yiddish for

the first time in 20 years. He began composing folk legends, Hasidic tales,

and short stories about social issues.

The cosmopolitan city

of St. Petersburg was home to many Jewish cultural institutions that were

founded to preserve Jewish folk culture in the Russian language. Ansky

threw himself into this cultural effort, working for the Jewish Literary

Society, and the Russian-Jewish monthly Evreiski Mir (he became

literary editor), and the Society for Jewish Folk Music. For the first

time, he was making a living as a writer. Ansky traveled around the Pale,

giving lectures that spread the word about Jewish folklore,

Yiddish literature and theater, and the war —

as well as the virtues of revolution.

During the years 1911-1914,

Ansky traveled through the villages of Volhynia and Podolia, as head of

the Jewish ethnographic expedition financed

by Baron Vladmir Guenzburg. During this expedition, he gathered material

and artifacts for the Jewish Historic-Ethnographic Society. This experience

was a central influence on Ansky's literary work, to which he brought

a deep appreciation of Jewish folk values. His knowledge of folklore inspired

and laid the foundation for his famous play The

Dybbuk, which he wrote in both Russian and Yiddish.

The ethnographic expedition

was cut short by WW I. Alarmed by the stricken state of the Jews

of Galicia who were being mercilessly persecuted and massacred by

the Russians, and frustrated by the lack of interest or urgency on the

part of Jewish philanthropists, Ansky devoted himself to organizing relief

committees for Jewish war victims. He embarked for the war zone while

lobbying and pulling strings with all of the contacts he had.

In 1917, Ansky was

elected to the All-Russian Constituent Assembly as a Social-Revolutionary

deputy. The Russian Revolution spelled his final exile from Russia in

1918; he moved to Vilna where he worked tirelessly to preserve Jewish

culture, founding the Vilna Historic-Ethnographic Society and helping

establish the Vilna Union of Writers and Journalists. The Jewish executions

and pogroms in Vilna finally conquered Ansky's unflagging spirit; at the

close of the war he moved to Warsaw, where, at age fifty-six, he died

from a complication of pneumonia. The Vilna Troupe honored Ansky's memory

by finally staging The Dybbuk shortly after his death —

to great acclaim.

Ansky's Yiddish writings,

published posthumously by the Vilna intellectual community during the

years 1920-1925, include poems, plays, narratives, memoirs, folklore,

and three volumes of observations on the havoc wrought by World War I

among the Jewish communities of Galicia, Bukovina, and Poland. Ansky's

grave, which can be visited to this day in the Warsaw Jewish cemetery,

lies next to those of two other masters of Yiddish literature, I.L. Peretz

and Jacob Dinezon.

|

[1]

The Pale of Settlement was the territory within the borders of czarist

Russia where Jews were legally permitted to live, from 1791 to 1917.

The Pale covered an area of about 386,000 sq. mi. between the Baltic

Sea and the Black Sea. According to the census of 1897 nearly five

million Jews or 94% of the total Jewish population of Russia lived

in the the Pale; this constituted 11.6% of the general population

of the region. Jews were also restricted in their occupations, principally

to commerce and crafts. Nearly all the Jews in the Pale spoke Yiddish,

and Jewish/Yiddish literature and culture flourished there. [back]

[2]

Ansky also wrote a hymn called "To the Bund," which summarizes his

beliefs at the time:

Messiah

and Judaism--both have died,

Another Messiah has come:

The Jewish Worker (the rich man's victim)

Raises the flag of freedom. [back]

|

|

Beizer,

Mikhail, trans. Michael Sherbourne, The Jews of St. Petersburg

(Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society, 1989).

Encyclopedia

Judaica, "S. An-ski" and "An-ski Collections."

Roskies,

David G., "S. Ansky and the Paradigm of Return." in The

Uses of Tradition (New York: The Jewish Theological Seminary

of America, 1992).

Roskies,

David G., ed.,The Dybbuk and Other Writings (New York: Schocken

Books, 1992).

|

|