|

Egyptian,

Assyrian and Babylonian monuments depict the unique way various

peoples treated facial hair. The Semites appear with either thick

beards or thin, groomed ones; the Libyans have pointed beards;

while the Babylonians and Persians are represented with curly

and groomed beards. Sea Peoples, Hittites, Ethiopians, and most

Egyptians are portrayed as clean-shaven.

In ancient Israel

a long and well-groomed beard was considered a mark of distinction:

"It is like the precious oil upon the head running down upon

the beard, upon the beard of Aaron that went down to the skirts

of his garments."[1]

The Hebrews

avoided shaving the beard and the hair of the head. The nazir,

a type of priest, was forbidden to shave the hair of his head

and the edges of his beard. [2]

Shaving is also a part of ritual purification.[3]

A shaved head and beard was a sign of disgrace,[4]

and one case of humiliation by shaving half a beard is recorded.[5]

Shaving was identified with the spontaneous plucking of the beard,

an expression of great sorrow.[6]

The prohibition against cutting the hair and shaving was later

established as a fundamental mourning practice.

|

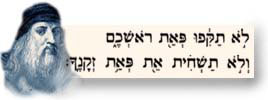

You

shall not round the side-growth of your head

nor destroy the side-growth of your beard. …."

(Lev. 19:27)

|

The Torah

forbids cutting the "corners" (sidelocks) of the hair:

"You shall not round the side-growth of your head [pe'at

rosh'hem] on your head, or destroy the side-growth [pe-at

zekaneha] of your beard. You shall not make gashes in your

flesh for the dead,or incise any marks on yourselves…."[7]

Interestingly, the Hebrew word for "side growth" is

pe'ah, the same word used earlier in verse 9 to designate

the corner or edge of a field: "When you reap the harvest

of your land, you shall not reap all the way to the edges of your

field {pe'at sad'ha]. According to the Talmud pe'at

rosh'hem refers to the hair on the temple, from the back of

the ears to the forehead;[8]

depilatory powder, scissors, or an electric shaver, permitted

for shaving the face, may not be used on this area.

While the Torah's

intention seems to be to differentiate Israelites from other peoples,

or to avoid imitating a particular pagan custom, evidence from the

Middle Ages indicates that Jews generally followed the customs of

the countries in which they lived. It appears that trimming the

beard was customary in Christian countries, especially Italy, while

Jews residing in Moslem lands allowed their beards to grow naturally

as was the custom there. Parchon, the 12th century Italian Jewish

grammarian, condemned the Jews of Christian lands who let their

hair grow long. In Italy, Jewish parents cut their boys' hair so

that a curl remained on the top and they would not stand out among

Christian boys.

Israel Abrahams

writes in Jewish Life in the Middle Ages that while the

Jew would not wear the Moslem's "heaven-lock," he was

by no means devoted to the love-lock pendant from his ears, which

became in the Middle Ages a distinctly Jewish feature. In northern

Africa the Jews satisfied themselves by leaving a single hair

to represent the "corner." Shaving was common in Majorca

in the fifteenth century. Later in Leghorna, a takana (rabbinical

injunction) was introduced to enforce the use of scissors or a

depilatory in preference to a razor.

In contemporary

times, ultra-Orthodox men grow their beards long, while modern-Orthodox

men use an electrical shaver, relying on the a widely accepted

pesak-halakha (religious ruling).

|