The

most hallowed of the domestic prayer experiences were those that accompanied

every meal, especially the Sabbath and festival meals, when the whole family

participated in the recital of the prayers. The opening benediction before

the meal is the brief blessing in which God is praised and thanked for "bringing

forth bread from the earth." Bread,

in this blessing, is the symbol of all food and includes the whole meal irrespective

of the variety of dishes served. The recitation of this blessing, known as

the Hamotzi (Who brings forth [bread from the earth]), was already

widespread in rabbinic times. Thus, an innkeeper is quoted in the Midrash

as saying to a fellow Jew: "When I saw that you ate without washing your hands

and without a blessing, I thought you were an idolater."[1] Bread,

in this blessing, is the symbol of all food and includes the whole meal irrespective

of the variety of dishes served. The recitation of this blessing, known as

the Hamotzi (Who brings forth [bread from the earth]), was already

widespread in rabbinic times. Thus, an innkeeper is quoted in the Midrash

as saying to a fellow Jew: "When I saw that you ate without washing your hands

and without a blessing, I thought you were an idolater."[1]

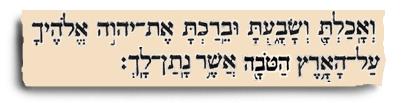

The devotions after the meal made up for the brevity of the Hamotzi.

They constitute a well-constructed and deeply moving prayer unit of four bulky

benedictions. In these benedictions the Jew thanks God in accordance with

the biblical injunction: "When you have eaten your fill, give thanks to the

Lord your God for the good land which He has given you."[2]

Accordingly, the first benediction thanks God for the blessing of food, and

the second benediction for "the good land" that He gave to Israel as an inheritance.

The third benediction thanks God for His merciful restoration of Jerusalem.

To be sure, Jerusalem was in ruins; nonetheless, the benediction is in the

present tense — "who rebuilds Jerusalem." The redemption

of Israel will materialize at any moment, perhaps at the very moment when

the benediction is being recited....

The three initial benedictions of Birkat ha-Mazon (the Blessing for

the Food, often translated Grace after Meals) are among the most ancient

prayers in the Jewish liturgy. The rabbis emphasize their antiquity by ascribing

them to Moses, Joshua and King Solomon, respectively. The Talmud teaches:

Moses instituted

for Israel the [first] benediction [of the grace] —

"Who feeds" — at the time when the manna descended

for them. Joshua instituted for them the [second] benediction of the land

when they entered the land. David and Solomon instituted the [third] benediction

which closes "Who builds Jerusalem."[3]

A fourth benediction, called "Ha-tov veha-meitiv" (Who is good and

does good) is a later addition, attributed by the rabbis to the period immediately

after the Bar Kokhba rebellion in the second century. At that time the remnants

of the Jewish people were threatened with extinction through a pestilence

caused by the many corpses strewn everywhere; when the Romans granted permission

to bury the dead, this benediction was instituted, thanking God for not

permitting Israel to perish.

With the passage of time the Birkat ha-Mazon expanded considerably

beyond the initial core. Thanksgiving prayers for a number of additional

blessings were incorporated in the first three benedictions. Among the divine

blessings for which thanks are expressed are the gifts of the Torah, the

covenant of Abraham, and the dynasty of David, one of whose descendants

will be the Messiah, according to tradition.

But it was the fourth

benediction that grew largest in size. People took more liberties with

it because it was the latest of the benedictions to be officially incorporated

into the Birkat ha-Mazon. A number of general supplications were

added to this benediction, each of which starts with the words "Ha-rahaman"

(May the all-merciful). The number of these Ha-rahaman verses vary

in different communities: Maimonides (Spain & Egypt, 12th cent.) lists

three; Yemenite Jews, four; Mahzor Vitry (France, 12th cent.),

twelve; the Sephardim, eighteen; the Roman rite, twenty-two; and modern

Ashkenazi custom, nine.

For the Sabbath a special prayer was added, and for the festivals and

New Moon days prayers were borrowed from the liturgy. At circumcisions

and wedding feasts, poetic interpolations are customary. There is also

a special form or recitation in the house of mourning. When three or more

adults[4]

participate in a meal, the Birkat ha-Mazon becomes a formal group

service and the leader opens with an invocation, "Rabbotai nevarekh" (Gentlemen,

let us say grace), a sort of official call to worship to which the participants

respond. The custom and formula are ancient and according to the Talmud,

as old as Shimeon ben Shetah.[5]

By the end of the geonic period (mid-sixth to mid-eleventh century), this

service had not only been formulated but also fully accepted. Only minor

accretions were added in the subsequent centuries. To this day the Birkat

ha-Mazon services those Jews who choose to express their gratitude

to God for the sustenance He has provided, for the world and its bounty.

|

[1]

Numbers Rabbah 20:21 [back]

[2] Deut. 8:10 [back]

[3] Babylonian Talmud Berakhot 48b [back]

[4] The invitatory formula is known as Zimmun,

while three or more adults who have eaten together represent a mezuman.

Traditionally, those counted are male, although according to the Talmud

three or more women who have eaten together should also recite Zimmun

(Berakhot 45b). Later rabbinic authorities were divided as to whether

a woman could be counted together with the men. The great majority

of non-Orthodox count participants of either sex (of Bar/Bat Mizvah

age), while Sephardim permit a boy over six who understands what he

is saying to be counted. [back]

[5] Jerusalem Talmud Berakhot 7:2 [back] |

|

From:

Abraham Millgram's Jewish Worship (JPS, 1971, 1975). This

article, based on Millgram's presentation of the development of

Jewish liturgy, has been expanded for the purposes of this webzine

edition. From:

Abraham Millgram's Jewish Worship (JPS, 1971, 1975). This

article, based on Millgram's presentation of the development of

Jewish liturgy, has been expanded for the purposes of this webzine

edition.

|

|