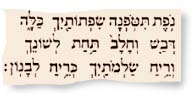

The beautiful poem that takes up all of Chapter 4, ending in the first verse

of Chapter 5 provides an apt illustration of the poetic art of The Song

of Songs. I will look closely in this article at the wonderful transformations

that the landscape of fragrant mountains and gardens undergoes from line 11

to the end of the poem. The first mountain and hill in line 11 are metaphorical,

referring to the body of the beloved or, perhaps, as some have proposed, more

specifically to the mons veneris.

It

is interesting that the use of two nouns in the construct state to form a

metaphor (“mountain of myrrh,” “hill of frankincense”)

is quite rare elsewhere in biblical poetry, though it will be come a standard

procedure in postbiblical Hebrew poetry. The natural manner with which the

poet adopts that device here reflects how readily objects in the Song of

Songs are changed into metaphors. The Hebrew for “frankincense”

is levonah, which sets up an intriguing faux raccord with “Lebanon,”

levanon, two lines down. From the body as landscape — an identification

already adumbrated in the comparison of hair to flocks coming down from the

mountain and teeth to ewes coming up from the washing – the poem moves

to an actual landscape with real rather than figurative promontories. It

is interesting that the use of two nouns in the construct state to form a

metaphor (“mountain of myrrh,” “hill of frankincense”)

is quite rare elsewhere in biblical poetry, though it will be come a standard

procedure in postbiblical Hebrew poetry. The natural manner with which the

poet adopts that device here reflects how readily objects in the Song of

Songs are changed into metaphors. The Hebrew for “frankincense”

is levonah, which sets up an intriguing faux raccord with “Lebanon,”

levanon, two lines down. From the body as landscape — an identification

already adumbrated in the comparison of hair to flocks coming down from the

mountain and teeth to ewes coming up from the washing – the poem moves

to an actual landscape with real rather than figurative promontories.

If domesticated or in any case gentle animals populate the

metaphorical landscape at the beginning, there is a new note of danger or

excitement in the allusion to the lairs of panthers and lions on the real

northern mountainside. The repeated verb “ravish” in line 16, apparently

derived from lev, “heart,” picks up in its sound (libavtini)

the inter-echo of levonah (frankincense) and levanon (Lebanon),

and so triangulates the body-as-landscape, the external landscape, and the

passion the beloved inspires.

The last thirteen lines of the poem, as the speaker moves

toward the consummation of love intimated in lines 26-29, reflect much more

of an orchestration of the semantic fields of the metaphors: fruit, honey,

milk, wine, and, in consonance with the sweet fluidity of this list of edibles,

a spring of fresh flowing water and all the conceivable spices that could

grow in a well irrigated garden. Lebanon, which as we have seen has already

played an important role in threading back and forth between the literal and

figurative landscapes, continues to serve as a unifier.

The

scent of the beloved’s robes is like Lebanon’s scent (line 18),

no doubt because Lebanon is a place where aromatic trees grow, but also with

the suggestion (again fusing figurative with literal) that the scent of Lebanon

clings to her dress because she has just returned from there (lines 13-15).

“All aromatic woods” in line 21 is literally in the Hebrew “all

the trees of levonah,” and the echo of levonah-levanon is carried forward

two lines later when the locked spring in the garden wells up with flowing

water (nozlim, an untranslatable poetic synonym for water) from the

mountain streams of Lebanon. The

scent of the beloved’s robes is like Lebanon’s scent (line 18),

no doubt because Lebanon is a place where aromatic trees grow, but also with

the suggestion (again fusing figurative with literal) that the scent of Lebanon

clings to her dress because she has just returned from there (lines 13-15).

“All aromatic woods” in line 21 is literally in the Hebrew “all

the trees of levonah,” and the echo of levonah-levanon is carried forward

two lines later when the locked spring in the garden wells up with flowing

water (nozlim, an untranslatable poetic synonym for water) from the

mountain streams of Lebanon.

There

is a suggestive crossover back from the actual landscape to a metaphorical

one. The garden at the end that the lover enters – and to “come

to” or “enter” often has a technical sexual meaning in biblical

Hebrew – is the body of the beloved; one is not hard put to see the physiological

fact alluded to in the fragrant flowing of line 25 (the same root as nozlim

in line 23) that precedes the enjoyment of luscious fruit. There

is a suggestive crossover back from the actual landscape to a metaphorical

one. The garden at the end that the lover enters – and to “come

to” or “enter” often has a technical sexual meaning in biblical

Hebrew – is the body of the beloved; one is not hard put to see the physiological

fact alluded to in the fragrant flowing of line 25 (the same root as nozlim

in line 23) that precedes the enjoyment of luscious fruit.

Although we know, and surely the original audience was intended to know, that

the last half of the poem conjures up a delectable scene of love’s consummation,

this garden of aromatic plants, wafted by the gentle winds, watered by a hidden

spring, is in its own right an alluring presence to the imagination (before

and after any decoding into a detailed set of sexual allusions). The poetry

by the end becomes a kind of self-transcendence of double meaning: the beloved’s

body is, in a sense, “represented” as a garden, but it also turns

into a real garden, magically continuous with the mountain landscape so aptly

introduced at the midpoint of the poem.

|

From:

The Art of Biblical Poetry by Robert Alter (Basic Books, 1985).

Reprinted by permission of the author. From:

The Art of Biblical Poetry by Robert Alter (Basic Books, 1985).

Reprinted by permission of the author. |

|

Robert Alter is professor

of Hebrew and Comparative literature at the University of California

at Berkeley. He has written broadly on biblical and modern Hebrew literature. |

|