|

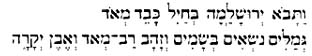

The Book of Kings describes how Solomon welcomed

to Jerusalem the Queen of Sheba, whose kingdom was in South Arabia. She came

“with a very great retinue, with camels bearing spices, and very much gold,

and precious stones.”[1]

Although scholars debate whether in fact this story is 100% factual, it is accurate

that during this period (tenth century BCE), the spice trade between African

countries and southern Arabia, and between Syria and the Mediterranean lands,

was already brisk.

From

ancient times, perfumes and spices were popular commodities in the near East,

and the spice trade was a particularly active one. From both the Bible and other

classical sources it appears that the valuable plants from which the coveted

aromatic resins, incense, spices, and medicinal potions were produced, were

grown mainly in the kingdoms of southern Arabia. From this area, major land

and sea trade routes branched out to all the great trading centers of the ancient

world. From

ancient times, perfumes and spices were popular commodities in the near East,

and the spice trade was a particularly active one. From both the Bible and other

classical sources it appears that the valuable plants from which the coveted

aromatic resins, incense, spices, and medicinal potions were produced, were

grown mainly in the kingdoms of southern Arabia. From this area, major land

and sea trade routes branched out to all the great trading centers of the ancient

world.

King Solomon had inherited from his father David a kingdom which

extended from the Euphrates (including Syria and Transjordan) to the border

of Egypt. This dominion brought with it direct economic benefits and political

sway, such as tributes in the form of precious metals and raiment, spices and

horses.[2] More significantly,

however, it gave him control of the major transport routes between Egypt, Mesopotamia

and Anatolia (international routes known as “Via Maris” and “King’s

Highway”), routes to the south of Arabia, as well as a land link between

the Mediterranean and the Read Sea.

Along

these routes Solomon developed extensive land and sea trade, bringing his kingdom

tremendous economic advantage and greatly enriching the treasuries of his kingdom.[3]

It has been suggested that the fortresses built in southern Israel during the

tenth century BCE were constructed during Solomon’s reign to protect the

spice caravans passing along the caravan routes, from south to north. Along

these routes Solomon developed extensive land and sea trade, bringing his kingdom

tremendous economic advantage and greatly enriching the treasuries of his kingdom.[3]

It has been suggested that the fortresses built in southern Israel during the

tenth century BCE were constructed during Solomon’s reign to protect the

spice caravans passing along the caravan routes, from south to north.

Israel Museum curator Michal Dayagi-Mendes writes in her essay The Spice

Trade:[4] “Although

all these trade routes were well established, the transportation of perfumes

and spices was still long and hazardous. Many dangers lurked along the desert

routes for the spice caravans, and for the ships there were the various perils

of the sea, pirates among them. In addition, heavy taxes were imposed on carriers

of spices, especially on the overland caravans. Natural historian Pliny records:

“Fixed portions of frankincense are also given to the priests and the king’s

secretaries, but beside these the guards and their attendants and the gate-keepers

and servants also have their pickings. Indeed, all along the route they keep

on paying, at one place for water, at another for fodder or the charges for

lodging... So that expense mount up to 688 denarii per camel before the Mediterranean

coast is reached.”[5]

"It is no wonder that under such conditions, the prices of perfumes

and spices soared to exceeding heights....”

In later centuries, in their Diaspora settlements in the East

Mediterranean and Near East, Jewish merchants continued to trade in spices (as

well as other luxury goods). Although the Syrians at first led this trade, the

Jews took the leading position after the Arabs had conquered the Syrian coast.

They moved such commodities as musk, aloes, camphor and cinnamon from the Far

East along the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean trade routes and ports; these

activities were flourishing in the 11th to 13th centuries, as attested to in

genizah [6] documents

and responsa[7] from

the period.

With

the Turkish conquest, the Eastern routes fell into disuse. Christians became

more active in overseas trade, and they restricted the commercial activities

of the Jews; Italians soon replaced the Jews as intermediaries with the Orient.

By the sixteenth century, political and economic processes — including the

growing trade with the New World, the opening of a direct route to East India

by the Portuguese, and the subsequent development of Portuguese and French maritime

trade with India and China — moved Jewish merchants back into the arena

of spice trade. With

the Turkish conquest, the Eastern routes fell into disuse. Christians became

more active in overseas trade, and they restricted the commercial activities

of the Jews; Italians soon replaced the Jews as intermediaries with the Orient.

By the sixteenth century, political and economic processes — including the

growing trade with the New World, the opening of a direct route to East India

by the Portuguese, and the subsequent development of Portuguese and French maritime

trade with India and China — moved Jewish merchants back into the arena

of spice trade.

In

the mid-sixteenth century, the New Christian Mendes family came to control a

major part of the commerce in pepper and other spices in northern Europe (the

largest market in Europe at that time). In the seventeenth and early eighteenth

centuries, Jews were trading actively in spices from Yemen and India, from Lisbon

(and following the expulsion from Spain and Portugal) and Amsterdam, serving

as agents in the European trading companies as well as independent merchants. In

the mid-sixteenth century, the New Christian Mendes family came to control a

major part of the commerce in pepper and other spices in northern Europe (the

largest market in Europe at that time). In the seventeenth and early eighteenth

centuries, Jews were trading actively in spices from Yemen and India, from Lisbon

(and following the expulsion from Spain and Portugal) and Amsterdam, serving

as agents in the European trading companies as well as independent merchants.

|

[1]

I Kings 5:1 [back]

[2] I Kings 5:1, 10:25 [back]

[3] I Kings 10:10, 25 [back]

[4] Perfumes and Cosmetics in the Ancient

World. Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 1989. [back]

[5] Pliny, Natural History XII:65 [back]

[6] A hiding room or storeroom, usually connected

with a synagogue, for the depositing of worn-out sacred books and sacred

objects. [back]

[7] Answers to questions of Jewish law and

observance written by halakhic scholars in reply to inquiries addressed

to them. [back]

|

|